14 Jun OLIVE CULTIVATION AS THE GUARDIAN OF THE FUTURE

Biodiversity, Landscape, and Climate

4th Science & Wine World Congress, Porto – Portugal

By Francesco Serafini, President The Garden of Peace

On May 29, I had the honor of being the keynote speaker for the opening of the session “Sustainable Practices in Olive Oil Production” at the 4th Science & Wine World Congress, held in Porto, Portugal.

An event where science, wine, olive oil, and sustainability came together to build a shared vision for the future.

Title: Olive Cultivation as the Guardian of the Future: Biodiversity, Landscape, and Climate

The olive tree does not grow: it meditates.

Its roots sink deeper into time than into soil.

To gaze upon it, is to sense it / listening to the wind—as if guarding some ancient secret.

It is a witness to the long time. To millennia. To patience itself.

The olive is not merely a tree. It is a living boundary between past and future, between the memories of our granparents and the challenges awaiting our children. A living creature that teaches us resilience, restraint, and the quiet strength of enduring things.

It is woven into our spirituality: cited in the sacred texts of all three Mediterranean monotheist religions—the Torah, the Bible, and the Quran—yet equally alive in Greek myths and contemporary poetry. It graces Byzantine mosaics, Renaissance masterpieces, and the proverbs of farmers.

But today, more than ever, we must learn to see it with new eyes.

For the olive tree holds answers to a crucial question:

How can we keep producing without destroying?

How can we inhabit the future without betraying the earth?

PATHS OF SUSTAINABILITY: From Biodiversity to Cultural Landscape

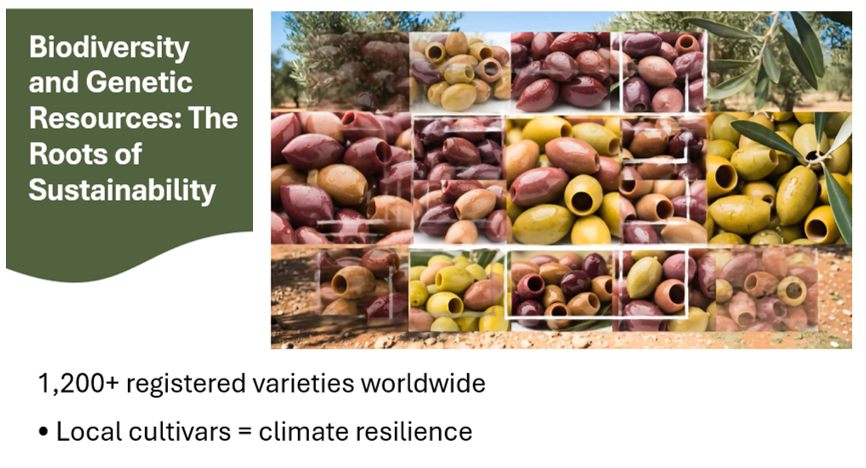

1. Biodiversity and Genetic Resources: The Roots of Sustainability

Sustainability begins at the roots. From genetics.

In the ability to select local, resilient, and intelligent varieties that coexist with the climate rather than fight against it.

The olive tree boasts a huge genetic heritage: over 1,200 registered varieties worldwide.

Each cultivar tells a story of a landscape, a culture. It is a fragment of agricultural biodiversity that we have a duty to preserve and enhance.

Too often, however, the varietal simplification imposed by mechanization and globalization has sacrificed this richness on the altar of efficiency. But today, the proper use of genetic resources is not just an act of conservation: it is an act of innovation.

It means:

- Choosing varieties adapted to climate change

- Enhancing resistance to drought, pests, and diseases

- Reducing reliance on chemical inputs

- Adapting production to the land, not the other way around

This is regenerative agriculture, not nostalgia.

Agronomic intelligence, not romanticism.

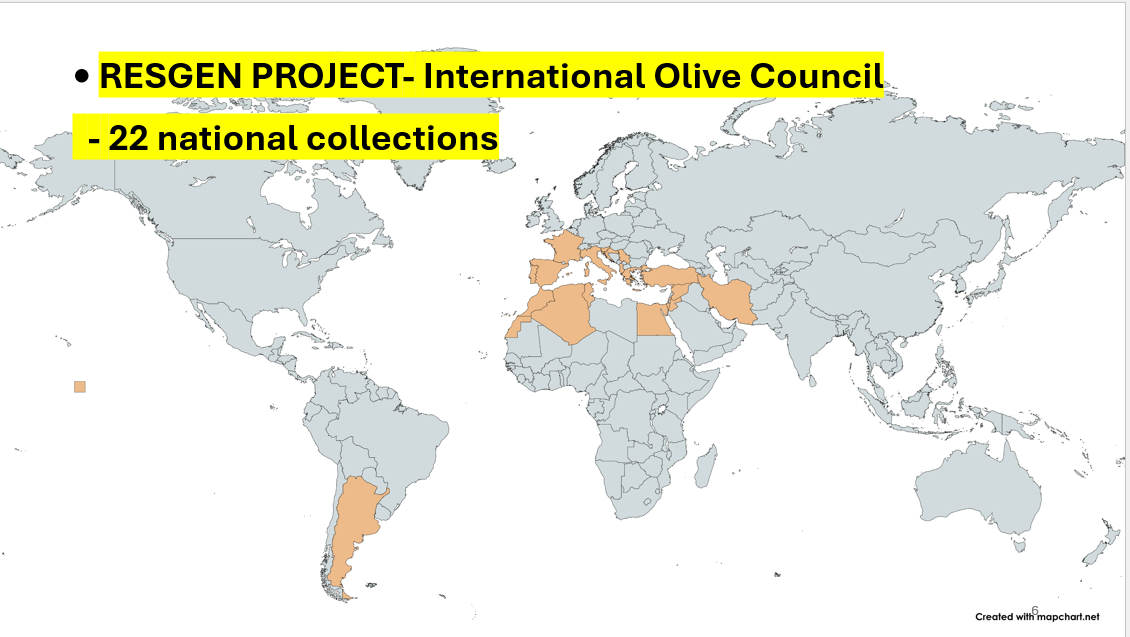

The project led by the International Olive Council, which I had the honour of coordinating, involved 22 countries across the Mediterranean and beyond.

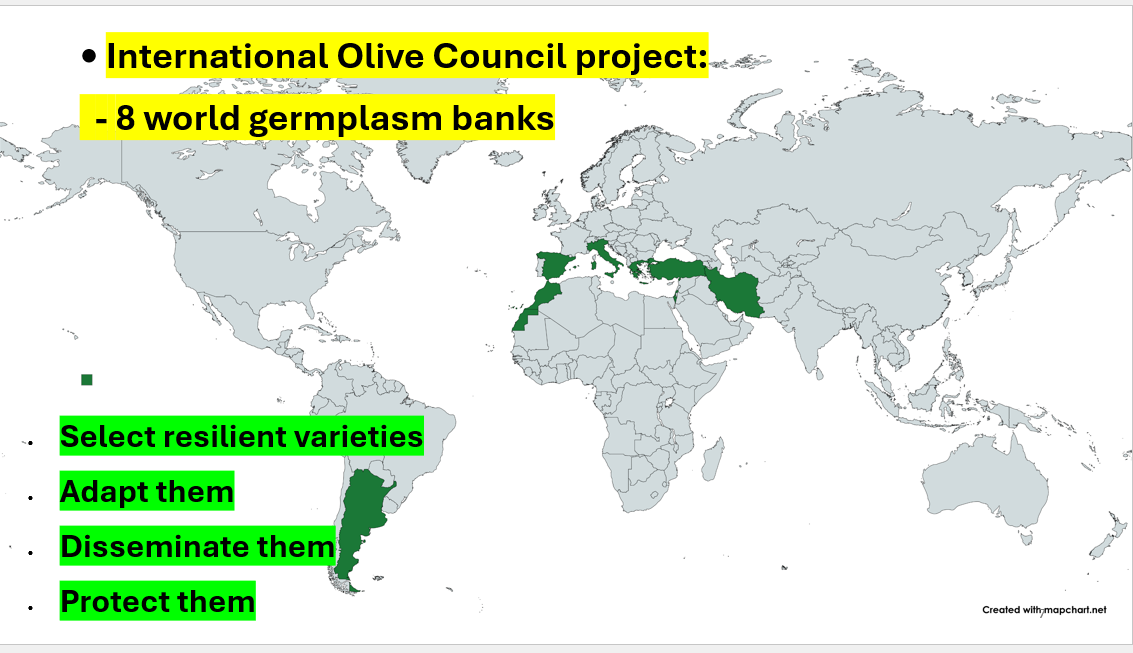

It has created 22 national collections and 8 world banks of olive germplasm, which today represent a real “living library”.

But preservation alone is not enough. We must study, use, and act:

- Select resilient varieties

- Adapt them

- Disseminate them

- Protect them

Because biodiversity, if it does not reach the fields, remains confined to museums.

The olive cultivation of the future needs varieties capable of withstanding ever-changing environmental and climatic conditions—and of confronting emerging phytosanitary threats, chief among them Xylella fastidiosa.

Climate change and emerging diseases threaten global olive production.

Genetic erosion – that is, the extinction of olive varieties – poses a high risk to the future of olive growing, as only about 15% of the world’s olive varieties are commercially exploited.

The existing genetic resources of the olive tree could offer valuable responses and solutions to both climate change and biotic stress, but they remain underused due to the limited development of pre-breeding activities and the lack of collaboration between germplasm banks and farmers and nurseries.

As a result, olive genetic resources remain unexploited and unused, merely conserved in germplasm banks.

The olive varieties held in international collections cannot remain “dormant”; they must be enhanced through specific actions that make them active, explorable, and transferable to end users.

The protection of autochtonous cultivars and the study of their agronomic behaviour in specific areas lay the groundwork for a reintroduction of olive cultivation based on strong biological and eco-physiological foundations.

This strategy can contribute to reducing the risks of hydrogeological degradation while at the same time adding significant landscape value to cultivation areas. Choosing cultivars with a strong territorial vocation allows for diversification in the organoleptic and nutritional profiles of local products.

Finally, it is important not to overlook the need to recommend cultivars with greater resistance to low temperatures, in order to reduce risks related to marginal or climatically sensitive growing areas.

2. The Olive Tree as a Climate Ally: Carbon Sequestration

It is no longer possible to talk about agriculture without talking about climate change.

NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) provides an interactive map that shows global temperature anomalies from 1880 to 2024.

The slide shows the change in global surface temperatures. Dark blue shows areas cooler than average. Dark red shows areas warmer than average. Short-term variations are smoothed out using a 5-year running average to make trends more visible in this map.

The debate on the extent of the anthropogenic contribution to climate change, compared to the natural factors that have always influenced the planet’s evolution, is still open. However beyond the causes, the urgent issue is how to mitigate the impacts of these changes. In this context, we can rely on a strategic ally.

The olive tree was recognized by UNESCO in 2019 as an essential resource for the planet: its Mediterranean roots have spread across five continents, making it an ally against climate change thanks to its ability to absorb more CO₂ than it emits.

Beyond its symbolic value, therefore, the olive tree also represents an important resource for our planet, thanks to its ability to adapt to climate change.

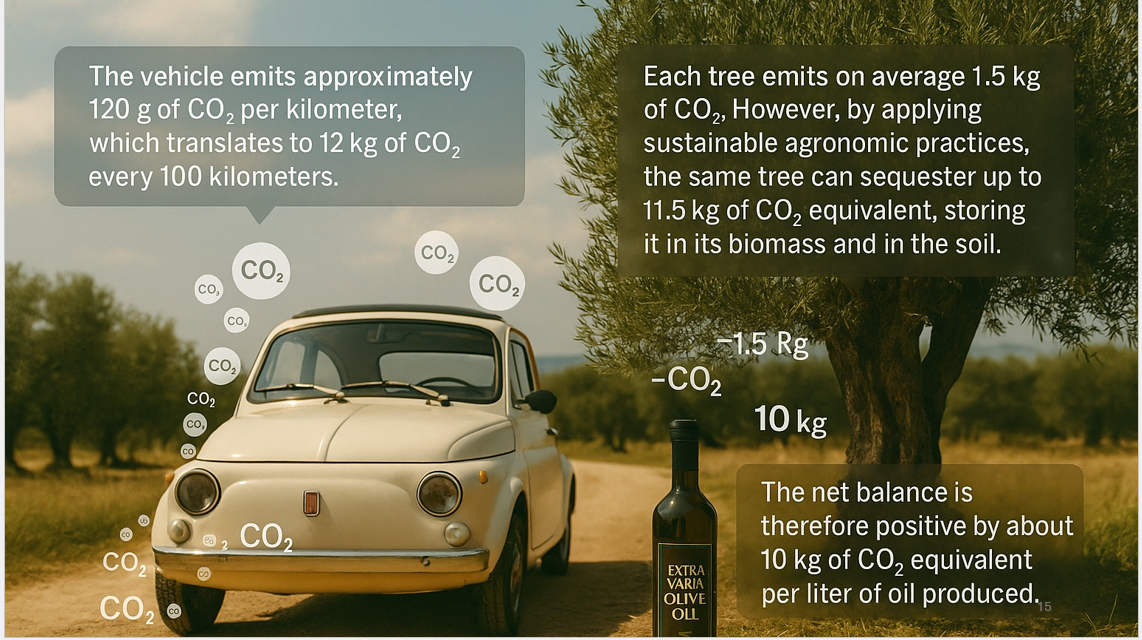

Would you be surprised if I told you that producing just one liter of virgin or extra virgin olive oil can offset the emissions of a Fiat 500 driving 100 kilometers? Incredible, isn’t it?

Now let’s take a closer look at how and why this is possible.

Plants absorb CO₂ from the atmosphere and release oxygen. A portion of the absorbed CO₂ returns to the atmosphere through respiration, while another part is stored in various organic components, thus creating a “carbon sink”.

Although agricultural plants have a shorter life cycle compared to forest species and do not permanently cover the soil with their canopy, they have a high carbon fixation potential, and the olive tree, among agricultural crops, is a species with a longer life cycle (in some cases spanning millennia), making it highly important for atmospheric CO₂ absorption.

And the olive tree, with its long life cycle, woody structure, and adaptabìlity, is one of the crops with the highest carbon sequestration potential.

But let’s get back to our FIAT 500. According to data provided by the manufacturer, the vehicle emits approximately 120 grams of CO₂ per kilometer, which translates to 12 kg of CO₂ every 100 kilometers.

Now let’s consider a 30-year-old olive grove: to produce one liter of virgin or extra virgin olive oil, each tree emits on average 1.5 kg of CO₂. However, by applying sustainable agronomic practices, the same tree can sequester up to 11.5 kg of CO₂ equivalent, storing it in its biomass and in the soil. The net balance is therefore positive by about 10 kg of CO₂ equivalent per liter of extra virgin and virgin olive oil produced. The reason I refer exclusively to virgin and extra virgin olive oils is that these are the only categories obtained solely through mechanical extraction methods, without the use of chemical solvents or refining processes.

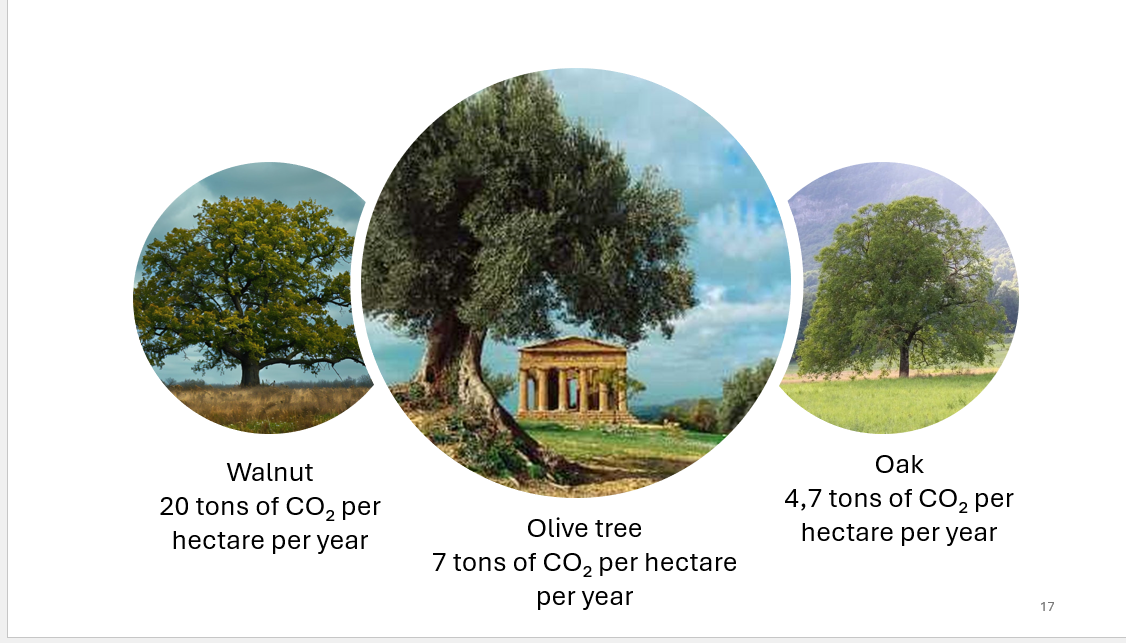

Several studies have compared various tree species to see which is best at “capturing” carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the atmosphere. It turns out that walnut or poplar plantations are the most efficient: they can store about 20 tons of CO₂ per hectare per year. Next comes the olive tree (with about 9.5 tons) and the oak (with about 4.7 tons per hectare per year).

But if we look at the amount of CO₂ captured by a single tree, considering also the fruits and pruned branches when buried into the soil, the olive tree performs very well: almost 29 kg of CO₂ per year per tree, which is six times more than the oak and nearly equal to walnut/poplar.

In fact, a study conducted by the IFAPA in Andalusia showed that one hectare of traditional olive grove can absorb between 2.5 and 5.6 tons of CO₂ per year.

In sustainable intensive systems, this figure can exceed 7 tons.

But the real carbon sink is the soil.

Soil managed correctly – with permanent ground cover, organic compost application, and no deep tillage – can increase its carbon content by up to 30% in ten years.

This means that a well-managed olive grove doesn’t just avoid pollution: it regenerates.

It regenerates the climate. It regenerates fertility. It regenerates hope.

The olive tree never ceases to amaze us; it has always been a gift for those who have approached its cultivation, and in this century, it will be an integral part of a system that must fight against man’s mistakes – once again, nature is a source of wisdom!

And it is essential that these ecosystem services be economically recognized.

Today, scientifically sound protocols are being developed to measure the carbon balance in olive groves, through collaborations with academic institutions and international networks.

The goal? To allow farmers to access voluntary carbon markets.

In Portugal as in Italy, France, Spain or Greece, an olive grower will be able to obtain carbon credits sellable to private and institutional entities, transforming landscape stewardship into income.

3. Europe and Future: Access to Funds and Value Recognition

Relying solely on individual efforts is no longer enough. The transition towards more resilient, regenerative and future-oriented agriculture requires structured tools and systemic support. In this context, the European Union now offers an unprecedented framework of financial and strategic opportunities.

Until recently, agriculture was viewed solely as a greenhouse gas-emitting sector. However, the 2023 IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report acknowledges its capacity to absorb carbon dioxide, opening new financial opportunities for industries such as olive cultivation.

Through the European Green Deal, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) 2023-2027 and key programs like Horizon Europe and LIFE, millions of euros have been allocated to support the ecological transition of the agri-food system.

How can olive farmers access these funds?

They must :

Demonstrate reduction of greenhouse gas emissions,

Adopt biodiversity-friendly practices,

Implement soil conservation and organic matter improvement

Integrate digitalization and traceability systems,

A New Vision of Value

What was once invisible – soil fertility, landscape beauty, biodiversity richness – can (and must) now become income, recognition and pride.

The future of olive growing also depends on this: the ability to seize these opportunities and network knowledge, territories and ideas. Today’s olive grower is not just a guardian of the land, but a strategic player in Europe’s ecological transition.

4. Landscape, Culture, Community: The Immeasurable Sustainability

Sustainability isn’t just numbers—it’s made of hands, stories, and landscapes. The olive tree carries memory, identity, and is a bridge between generations. Every olive grove is a living cultural landscape. When one disappears, we lose more than trees—we lose a vision of time that doesn’t rush.

I’ve met young people returning to the land and elders who speak to trees like old friends—both rooted in faith in the earth.

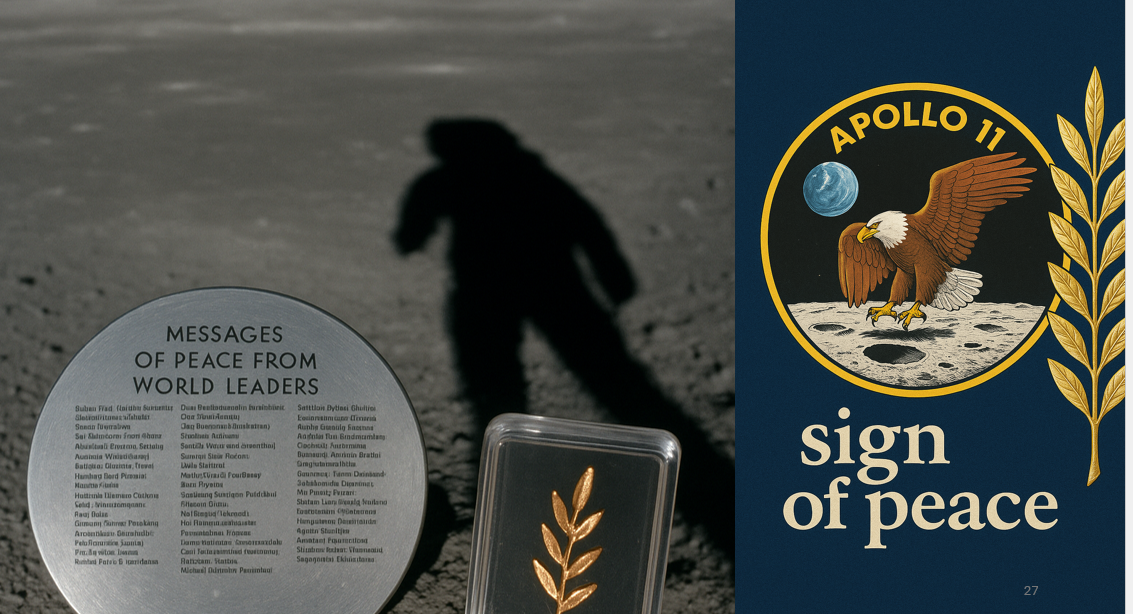

Even during the Moon landing, a golden olive branch symbolized peace.

Planting an olive tree is not just for harvest, but an act of faith in tomorrow. It’s a philosophy—an alliance between science and poetry, between roots and future.

But it demands bold choices, collaboration, and above all, love for the earth. Those who plant know they may not reap, but they leave a shadow, a message, an act of peace. And today, more than ever, that’s what we need: to cultivate hope.

I would like to conclude my remarks by introducing another key dimension of sustainability: social sustainability.

It is one of the three pillars of sustainable development, alongside environmental and economic sustainability. Social sustainability refers to the ability to ensure equity, well-being, and inclusion for all people, both now and in the future.

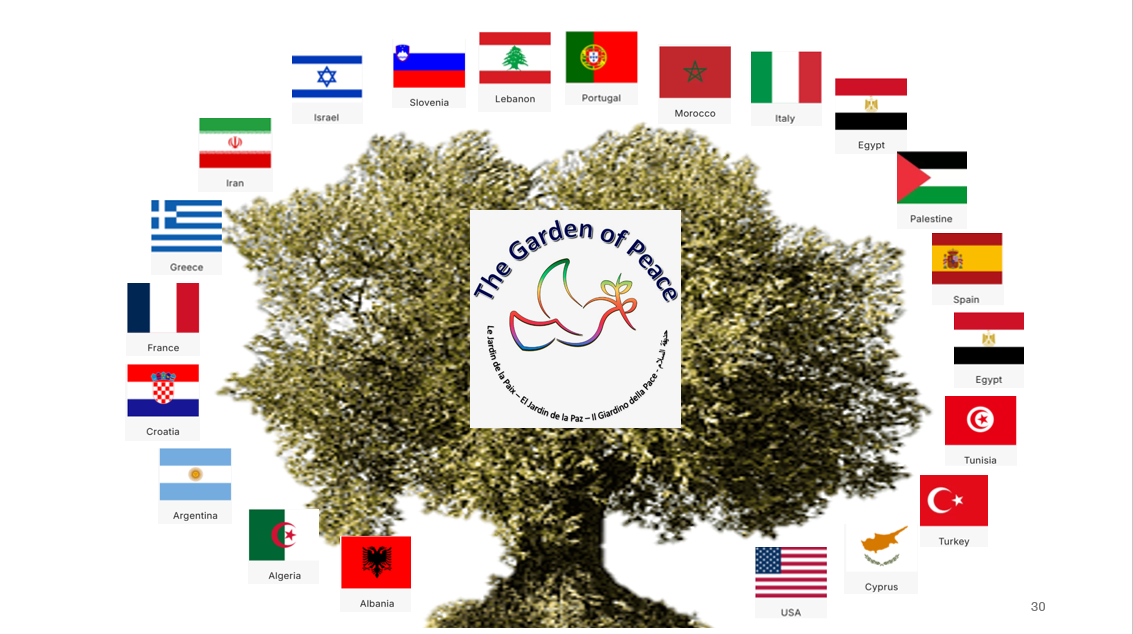

I have the honor of serving as president of the association The Garden of Peace, a non-profit organization that creates symbolic gardens composed of 21 varieties of olive trees, each originating from a different country. Through these gardens, we aim to unite nature, culture, and social commitment, creating physical and metaphorical spaces that represent:

- The possibility of coexistence among different cultures and religions;

- Resilience and peace, symbolized by the olive tree, a centuries-old emblem of life and tradition;

- An ecological and social message: just as olive trees grow together in the same soil, human beings too can live together in harmony.

Here are some of the gardens created by the association The Garden of Peace

Valley of the Temples, Sicily, Italy.

Alhambra, Granada, Spain.

International Olive Council, Madrid, Spain.

Academy of Music founded by Maestro Andrea Bocelli, Camerino, Italy.

Park of the Aljafería, Zaragoza, Spain.

Many other gardens have also been created in various symbolic sites, fostering synergies and shared activities.

This is the message I wish to leave to my children and, through them, to future generations: a call for peace, coexistence, and mutual care, conveyed through the universal language of nature.